The recent unveiling of Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy underlines the critical role hydrogen will play in the country’s journey towards a net-zero economy. With escalating concerns regarding climate change and the urgent need for sustainable energy solutions, this strategy aims to position Australia as a frontrunner in low-emission technologies. While the initiative is ambitious, its true effectiveness hinges on the clarity of its implementation and the government’s commitment to ensuring the strategy is not merely aspirational.

Federal Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen presented the updated strategy, marking a significant update from its predecessor initiated by former Chief Scientist Alan Finkel in 2019. The fundamental goal of the new strategy is to reduce the costs associated with producing green hydrogen—hydrogen generated through renewable energy. This is crucial not only for the domestic market but also for international engagement, aiming to create a strong competitive edge for Australia in the global hydrogen economy.

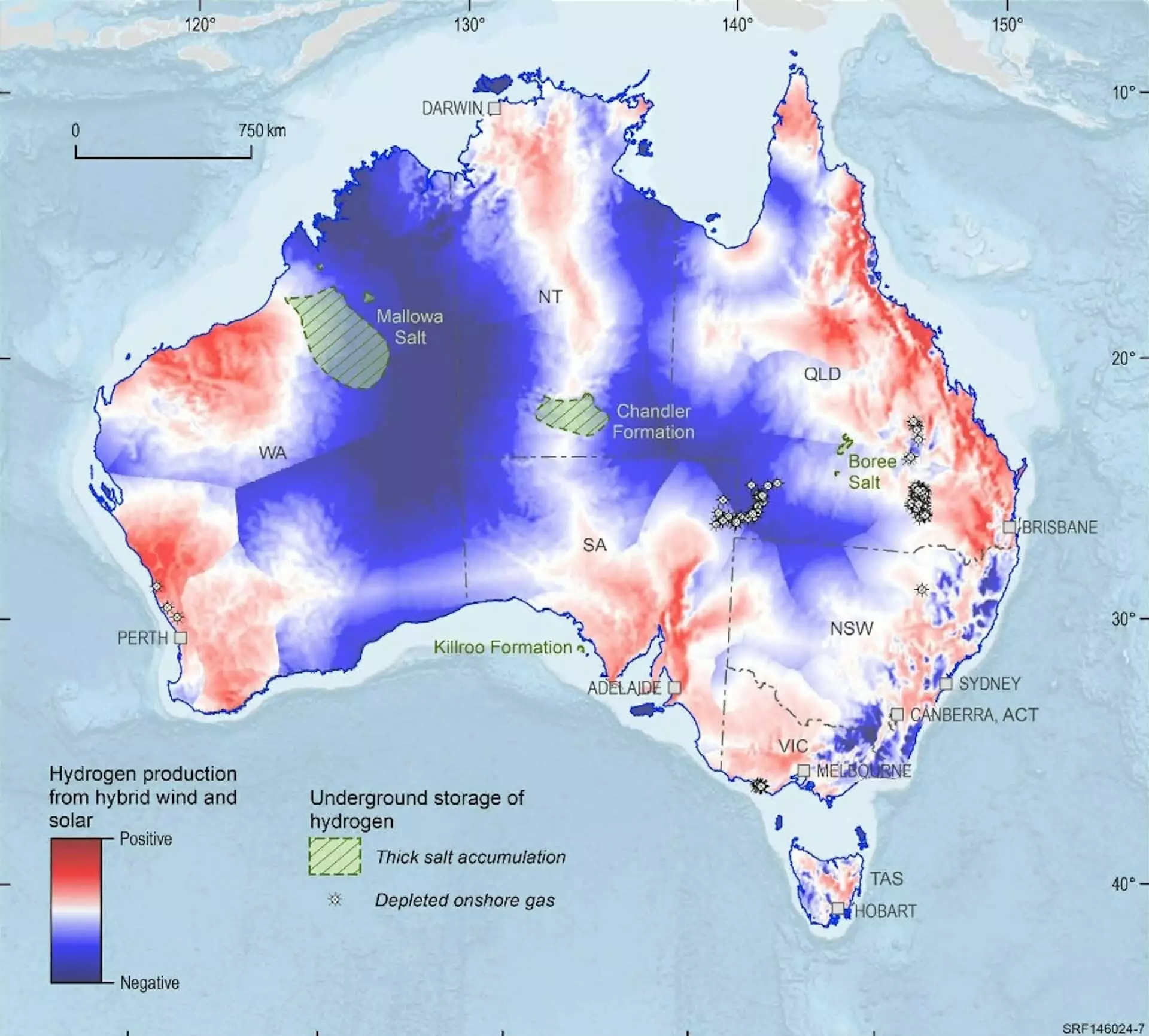

The importance of hydrogen cannot be overstated. As the smallest and most abundant element in the universe, hydrogen’s versatility extends from essential applications in manufacturing fertilizers and plastics to its potential as a clean energy carrier for the steel and chemical industries. Crucially, it also holds promise for storing electricity, presenting an opportunity for Australia to enhance its energy security and diversify its renewable energy portfolio.

The strategy sets forth ambitious production goals: achieving 500,000 metric tons of green hydrogen annually by 2030, and scaling that up to 15 million metric tons by 2050. Even more audacious are the “stretch targets” of 1.5 million tons by 2030 and 30 million by 2050. These targets are indicative of a serious intent to scale up production; however, the success of these initiatives will largely depend on the government’s ability to facilitate and support the necessary investment in infrastructure and technology.

One of the significant issues that arose from the previous strategy was the unrealistic target of producing hydrogen for less than $2 per kilogram, a figure that neglected the associated logistical challenges. By acknowledging the production and transportation hurdles, the new strategy reflects a more pragmatic approach. Yet, it still leaves open the crucial question of how the government plans to incentivize potential buyers to invest in hydrogen when they currently may not be inclined to pay the asking price.

A pivotal aspect of the updated strategy is its focus on three primary industries: iron, alumina, and ammonia, predicted to be significant consumer segments for hydrogen in export markets. Moreover, it explores additional areas where hydrogen can help reduce carbon emissions, such as aviation, shipping, and heavy freight. This flexibility demonstrates that the government is starting to grasp the technical and economic challenges associated with hydrogen as an energy source, especially in sectors where alternatives like electric vehicles may pose stronger competition.

However, to realize these goals, the strategy must provide clarity on how future funding and resources will be allocated. Stakeholders and investors are rightfully cautious about entering markets that may lack a clear policy framework and guidance. Will priority sectors receive preferential treatment for government support? How robust will oversight be for projects that fail to meet expectations? These uncertainties could deter investment if not clearly addressed.

The Case for Local Consumption Over Exports

Traditionally, the focus of Australia’s hydrogen strategy has been on exporting liquid hydrogen, initially targeting lucrative markets in Japan and South Korea. However, emerging interest appears to be shifting toward European markets, evidenced by a recent A$660 million agreement between Australia and Germany to secure hydrogen buyers in Europe. Despite this potential, hydrogen’s transportation presents considerable challenges, and this may warrant a reevaluation of the strategy’s export-focus in favor of bolstering domestic applications.

Compounding this complexity, there’s an ongoing discussion about community acceptance of hydrogen technologies. The memories of previous incidents involving hydrogen safety raise valid concerns among the public. Thus, while emphasizing the community benefits of job creation and regional economic diversification, the strategy must also address fears related to safety and environmental impact.

The new Hydrogen Strategy interacts with recent initiatives such as the $2 billion Hydrogen Headstart grants program and tax credits for hydrogen producers, which could play a role in achieving production goals. However, ensuring these measures do not support projects that lack long-term viability is imperative. Whether these incentives are tailored to focus on the most promising hydrogen applications remains to be seen.

In closing, the implementation and effectiveness of Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy will be critical for its long-term success. The strategy will undergo a review in 2029, with milestones such as the establishment of significant hydrogen projects, the signing of contracts, and substantial investments in renewable energy infrastructure serving as key indicators of progress. Should progress falter, a recalibration of goals and strategies may be necessary to maintain Australia’s commitments on the global stage in the green energy arena.