Lasers are ubiquitously recognized for their ability to produce a continuous beam of concentrated light. However, the landscape of laser technology is evolving to meet the demands of various scientific and industrial applications that require brief yet intense bursts of laser light. These short laser pulses are essential for high-precision processes, such as material machining and advanced imaging techniques capable of capturing events on an attosecond scale—an incredibly minute fraction of time (one quintillionth of a second). Recent advancements by a research team at ETH Zurich, headed by Professor Ursula Keller, have introduced the most powerful and shortest laser pulses to date. Their innovative work surpasses prior records and sets a new benchmark within the field of laser electronics.

The ETH Zurich team’s achievement is nothing short of astounding, with a recorded average power output of 550 watts, eclipsing previous benchmarks by an impressive 50 percent. This places them at the forefront of pulsed laser technology, emphasizing not only the intensity of the pulses produced but also their remarkable brevity. These newly developed pulses, which last less than a picosecond and are emitted at a staggering rate of five million pulses per second, produce peak powers of up to 100 megawatts. For context, this output can momentarily energize a hundred thousand vacuum cleaners, illustrating the extraordinary power these lasers possess.

For over two decades, Keller’s research focus has been on enhancing short-pulsed disk lasers, which utilize a thin crystal disk embedded with ytterbium atoms as the laser medium. However, the road to this groundbreaking achievement has been fraught with challenges. Repeated incidents of component damage within the laser apparatus presented significant setbacks, pushing the boundaries of engineering and scientific understanding. Each failure, however, served as a learning opportunity that ultimately contributed to the reliability and efficiency of short-pulsed lasers, making them increasingly viable for industrial applications.

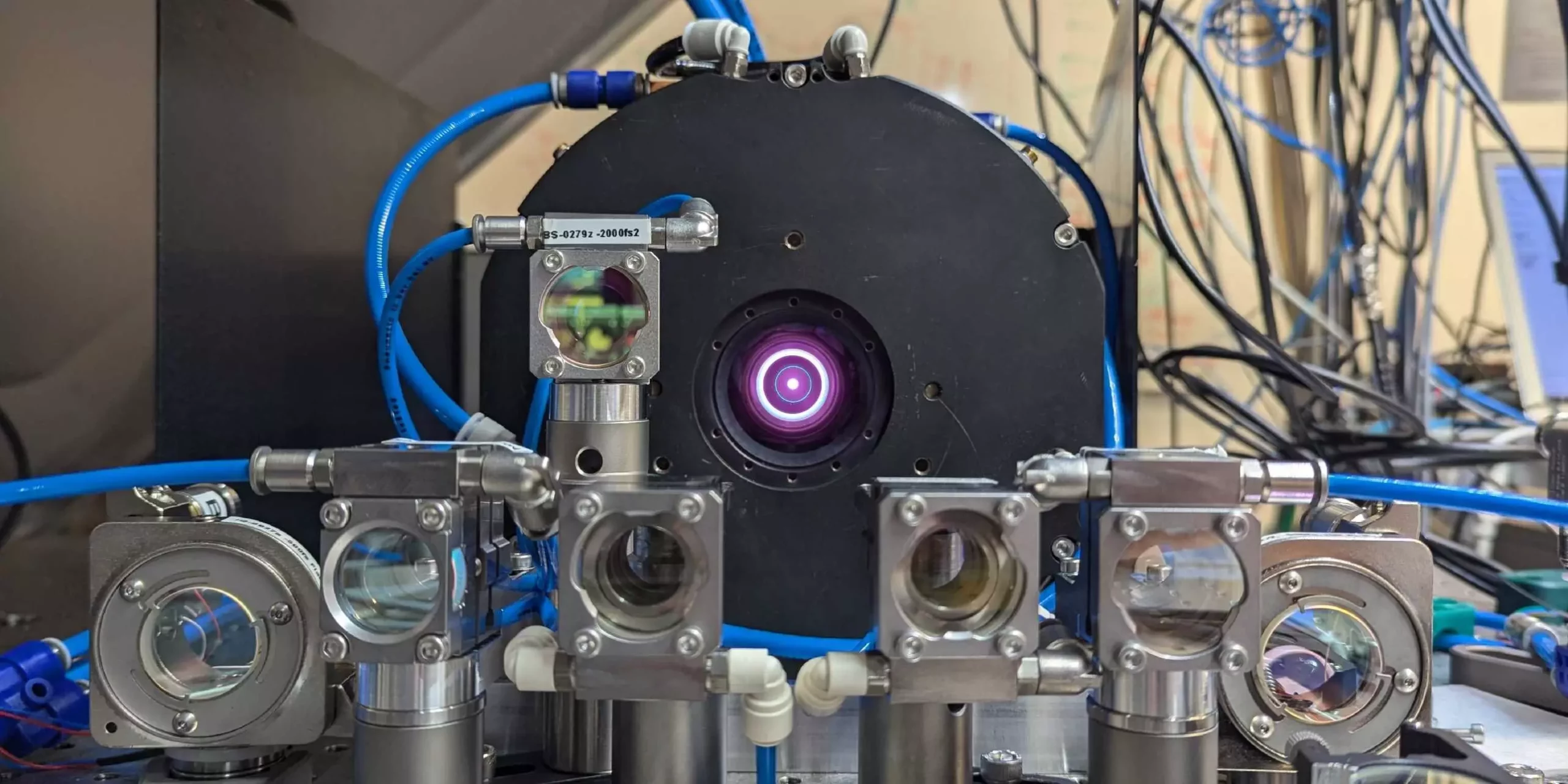

The unprecedented combination of high power and rapid pulse generation stemmed from two pivotal innovations introduced by the research team. Firstly, they implemented a sophisticated system of mirrors designed to circulate the light within the laser multiple times before it exits, amplifying light intensity and maintaining stability. This mirror arrangement is crucial, as it allows for significant power gains without destabilizing the laser.

The second key innovation lies with the Semiconductor Saturable Absorber Mirror (SESAM), initially conceived by Keller three decades prior. Unlike traditional mirrors, the SESAM’s reflectivity is responsive to the intensity of incoming light. This characteristic enables the conversion from a continuous light output to high-intensity pulses. An essential threshold must be surpassed for laser action to initiate; the SESAM efficiently reflects light that has circulated through the amplifying disk several times, propelling the system into a high-energy pulsed state.

Achieving such levels of power directly from the laser oscillator required the meticulous solving of multiple technical challenges. A significant hurdle involved integrating a delicate sapphire window with the semiconductor layer of the SESAM mirror. This integration ultimately improves the mirror’s functionality. Witnessing the laser’s ability to produce powerful pulses after overcoming these obstacles was described as a thrilling experience for Moritz Seidel, a Ph.D. candidate in the Keller lab.

Keller herself expressed excitement over the potential of these innovations, hoping the pulses can be further shortened to just a few cycles—critical for generating attosecond pulses that could revolutionize experimental physics.

The implications of these advancements in laser technology extend far beyond mere novelty. Keller foresees numerous applications emerging from the capabilities of these powerful pulse lasers, including the development of new frequency combs in the ultraviolet to X-ray range. Such tools could aid in crafting ultra-precise clocks and unlock new pathways for fundamental research—potentially challenging our existing understanding of natural constants.

Moreover, the ability to harness terahertz radiation through this advanced laser opens another avenue for material testing and analysis. This promises not only improved measurement precision but also enhances the potential use of laser oscillators as a more effective alternative to the traditional amplifier-based systems.

Keller and her team’s groundbreaking contributions mark a significant leap in laser technology. By demonstrating the viability of high-power laser oscillators, this research paves the way for future discoveries, emphasizing the role of innovation in pushing scientific boundaries. With such promising advancements, the world of laser technology is poised for an exciting future, rich with potential applications across various domains.