Quantum computing stands at the frontier of technology, promising a leap in computational power that could profoundly change various fields, from cryptography to drug discovery. However, the realization of a practical topological quantum computer remains a tantalizing prospect, currently confined to theoretical constructs. At the heart of this advanced computing paradigm lies a special kind of qubit that has yet to be experimentally manipulated. The recent advances in quantum mechanics and nano-scale electronic circuits have opened exciting avenues in this realm, particularly with the theoretical developments proposed by Professor Andrew Mitchell and Dr. Sudeshna Sen.

To grasp the significance of the recent findings regarding “split-electrons,” we must first revisit the fundamental concept of qubits, the building blocks of quantum information. Unlike classical bits, which are either 0 or 1, qubits can exist in superpositions of states, allowing quantum computers to process vast amounts of information simultaneously. This characteristic underpins the potential advantages quantum systems hold over traditional computing architectures.

However, for quantum computing to deliver on its promise, qubits must be stable and manageable. Topological qubits, in particular, are expected to be exceptionally resilient to errors due to their inherent properties governed by topology—a branch of mathematics that studies spatial properties preserved under continuous transformations. The creation of these qubits requires the manipulation of an elusive entity known as the Majorana fermion, a particle that exhibits behaviors akin to half an electron.

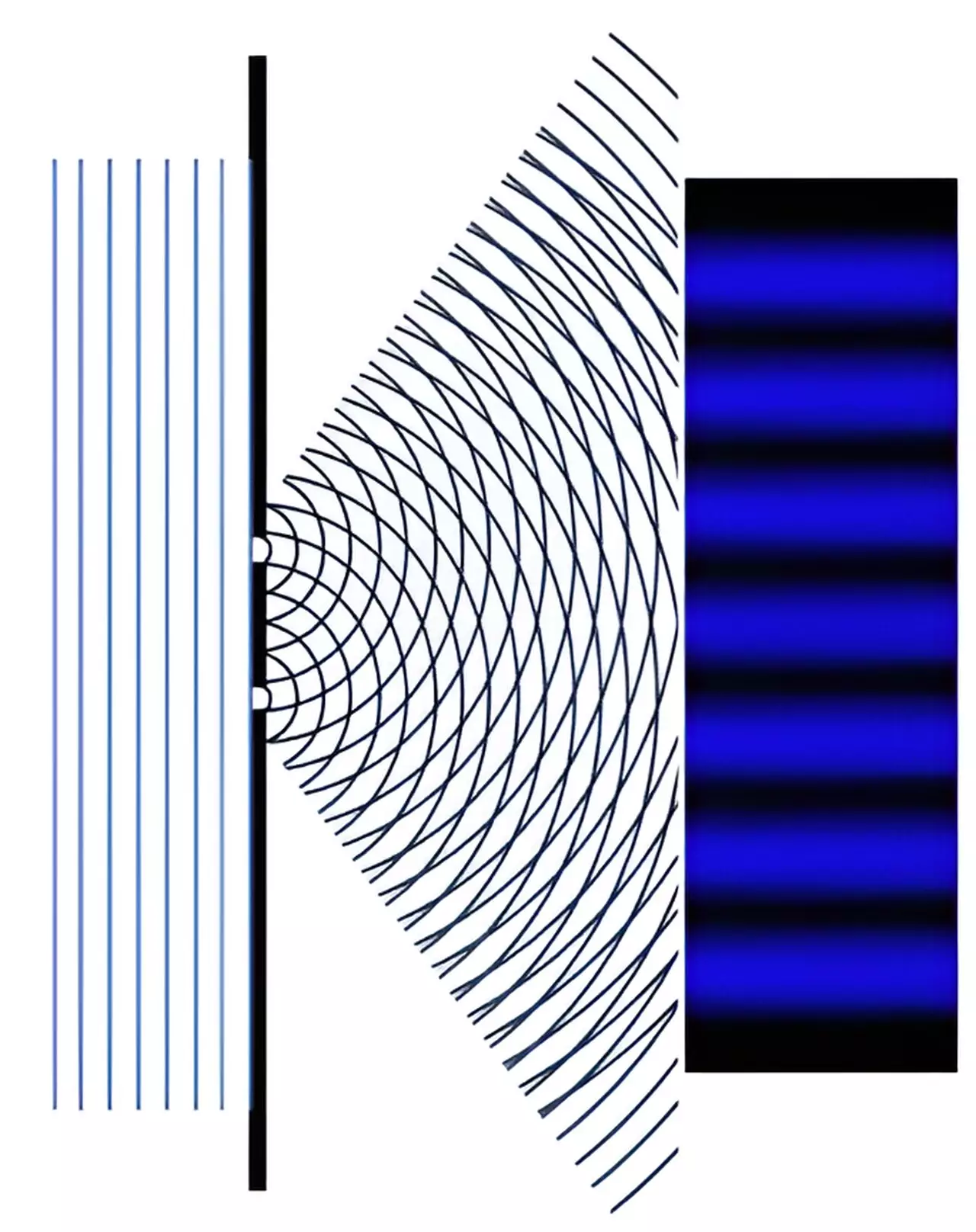

The new research by Professor Mitchell and Dr. Sen examines the intricacies of quantum interference among electrons within nano-scale circuits. At dimensions measured in nanometers, conventional physics gives way to quantum behaviors that are both bizarre and counterintuitive. An essential phenomenon within this context is quantum interference, where multiple quantum pathways can combine in ways that enhance or diminish the likelihood of certain outcomes.

Professor Mitchell describes an intriguing occurrence within their investigations: when electrons are forced into close proximity, they exhibit repulsion that alters the typical patterns of quantum interference. This interaction allows these electrons to act as though they have been split, leading to the emergence of what are termed “split-electrons.” The researchers propose that these anomalous behaviors might directly contribute to the formation of Majorana fermions in controlled environments, a significant step toward practical applications in quantum computing.

The concept of Majorana fermions, originating in the 1930s, faced decades of theoretical exploration without successful experimental verification. The prospect of generating these particles in electronic devices represents a substantial leap for quantum technology. As Professor Mitchell emphasizes, Majorana fermions could serve as foundational components for topological quantum computers.

In essence, if these discovered split-electron states can indeed be harnessed to produce Majorana fermions, this breakthrough could address one of the significant barriers towards realizing stable quantum computations. By utilizing their unique interactions and properties, researchers can potentially build systems that resist decoherence—a leading challenge in the quantum realm.

Despite the excitement surrounding these theoretical predictions, it is vital to recognize the distinction between theory and experimental validation. The intriguing parallels drawn between the behavior of electrons in nanoelectronic circuits and well-documented phenomena, such as the double-slit experiment, underscore the foundational principles of quantum mechanics but do not equate to concrete results.

Research in quantum mechanics often requires meticulous experimentation to transition from theoretical models into tangible applications. The current studies are a promising step, but further research will be critical to explore how these theoretical constructs can be reliably reproduced in laboratory environments.

The path to topological quantum computing, while still fraught with challenges, has begun to show glimmers of hope through cutting-edge research like that of Professor Mitchell and Dr. Sen. As quantum technologies advance, the exploration of phenomena such as split-electrons and Majorana fermions will be pivotal in shaping the future of computation.

In the face of uncertainty, the ongoing pursuit of knowledge in this field offers the tantalizing possibility that the next technological revolution in computing may be closer than we think, laying the groundwork for a new era of problem-solving capabilities that harness the quirks of quantum mechanics.